This article has nothing directly to do with SCA. It has to do with COVID-19 vaccines and efficacy rates. What I’ve learned does apply to understanding efficacy in SCA drug trials, and so I’m glad to have gone through this.

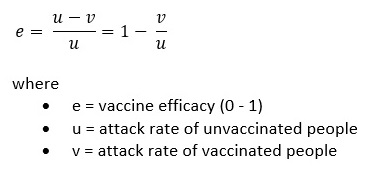

The efficacy of a vaccine pertains specifically to a Phase 3 drug trial and mathematically compares the outcomes of using a placebo to the outcomes of using the vaccine (i.e., it doesn’t directly, mathematically evaluate the vaccine against the disease but the vaccine against the placebo). I genuinely had a misunderstanding about this, which I cleared up and now document here.

The day that I heard the Pfizer vaccine trial had completed with a 95% efficacy, I immediately thought that it had failed. I oh-so wrongly thought that 95% meant that over 1,000 of the over 21,000 vaccinated trial participants experienced some kind of vaccination failure. I expected the stock market to tank, but instead it went up, and everyone seemed to think 95% represented good news. I had not studied vaccine efficacy at that point.

Let’s say efficacy is 90%. That doesn’t mean that vaccination failed in 10% of the vaccine administrations. It means that, in the trial, 10% of however many infections occurred were in those who received the vaccine. In other words, 90% of the infections were in those receiving the placebo, not the vaccine. This doesn’t tell us anything about the number of infections as a quantity or a ratio; it only measures the vaccine’s performance relative to the placebo’s performance.

Finding those willing to take a placebo and not the vaccine is not just a trial nicety but a necessity. To complete a Phase 3 vaccine trial, you need some unvaccinated participants to get the disease, otherwise the trial makes no sense. Even if the efficacy of the vaccine ends up being 100% (meaning no infections occurred in the vaccinated group), you need some in the placebo group to get the disease to prove that the no infections in the vaccinated group meant something. If being on the placebo is the same (or better) than being vaccinated, then the vaccine’s efficacy is 0%. (Really, for drug trials in general. Hello, Biohaven.)

The math

The math is about as simple as it can get, though here is an extraction, to make it even simpler:

Note that if the sizes of the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups are the same, the attack rate can be simplified to be the number of infections in that group.

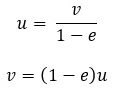

Solving for u and v:

More words behind the math

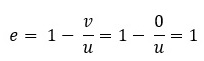

To make sure we understand the math, let’s look at when efficacy is 100%, 50%, 0%, and then back to 95%.

For a vaccine to be 100% effective in a trial, all infections must be in the placebo (unvaccinated) group, and you can’t have zero infections in the that group.

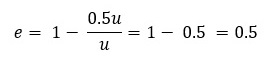

For a vaccine to be 50% effective in a trial, the number of infections in the vaccinated group must be 50% of the number of infections in the placebo (unvaccinated) group.

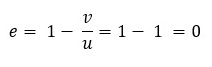

For a vaccine to be 0% effective in a trial, the numbers of infections in both equal-sized groups must be equal. I think we can assume that the number of infections in the vaccinated group won’t be higher than that of the placebo (unvaccinated) group.

How many infections must you have before you can make conclusions? I haven’t studied this closely enough to know, but let’s say you have one infection in the placebo (unvaccinated) group and zero in the vaccinated group. Can you claim 100% efficacy? Clearly not. I assume something reasonable is done to avoid situations like this.

So, back to:

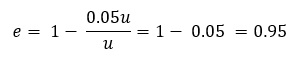

For a vaccine to be 95% effective in a trial, the number of infections in the vaccinated group must be 5% of the number of infections in the placebo (unvaccinated) group.

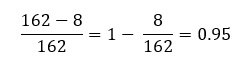

The Pfizer trial

The phase 3 Pfizer trial in 2020 had 43,448 participants and 170 infections (162 in the placebo [unvaccinated] group and 8 in the vaccinated group, where the group size was about 21,724). The 95% effective claim comes from:

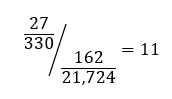

The low vaccinated infection rate of 8/21,724 (about 37 per 100,000) interests me. The placebo (unvaccinated) infection rate does not reflect the way things are in the wild (today, there have been about 27 million total U.S. infections, where:

The disease occurrence in the wild is about 11 times the rate in the study). I assume this means that people in the study were in general more precautious than those in the wild, which is perfectly reasonable.

Links

2020-11-20: I missed this earlier. It’s actually pretty good. From the New York Times, “…Vaccines Are 95% Effective. What Does That Mean?”

Leave a Reply